2. Objectives, Functions, Forms and Focal Points of Evaluations

This chapter is about the possible objectives and functions of evaluations. As different objectives and functions can be achieved through different forms of evaluation, we will look at the distinction between formative and summative evaluation. Since this chapter revolves around self-evaluation, we also want to identify the requirements that should be met to ensure the success of such an evaluation. In the final part of the chapter, we will then take a look at different evaluation focal points and dimensions.

2.1 What are the possible objectives and functions of evaluations?

If you are conducting an evaluation, you will generally be aiming to improve your own VE project (your own teaching). However, it may also be the case that your self-evaluation should or must have other functions, for example if other interest groups (e.g. donors/sponsors, superiors) are involved in the project. It is therefore important to be aware of these functions and objectives and to factor them into your considerations when designing your evaluation tools.

4. Activity:

Below are examples of various aspects that can be taken into account in VE project evaluations. Before turning over each card, think about which stakeholders and interest groups (students, teachers, (teachers as) researchers, sponsors/donors, educational institutions, e-learning department, IT department) might be interested in the relevant results and which functions they have in each case.

Evaluations should not only have a purely evaluative function; above all, they should form the basis for (further) developments (i.e. they should also help to obtain findings and promote further developments). However, evaluations often provide evidence of the effectiveness of a VE project and therefore also have a control or legitimation function (Arnold et al. 2018: 395ff.). In this regard, an evaluation may also help to “[…] check whether all participants have performed their tasks, whether their collaboration has worked and whether the learning outcomes have been achieved efficiently, and it may also help to legitimise or change the educational programme and the way it is used” (Arnold et al. 2018: 395).

It is important that you are aware of the respective functions of evaluations, because as useful as evaluations are (especially as a basis for the further development of VE projects), they can also have negative consequences. This can also happen, for example, if a test orientation arises because an evaluation at the end of a project only checks whether the (measurable) learning objectives have been achieved. You must also strike a careful balance between the effort involved in evaluations and the benefits they offer.

2.2 What forms of evaluation are there?

A distinction can be made between two overarching forms of evaluation:

A formative evaluation takes place during the course or project to directly identify the need for changes and adjustments; this form of evaluation is therefore conducted alongside the process and serves as a basis for planning and designing teaching (optimisation function; Döring/Bortz 2016: 990). However, a formative evaluation can also determine which learning steps have already been achieved and/or where there is still a need for learning (Arras/Kecker 2016: 393).

A summative evaluation is conducted at the end of a course or project and often focuses on the achievement of learning and teaching objectives (control and legitimation function; Döring/Bortz 2016: 990). A summative evaluation may also include selective performance assessments, e.g. at the end of a teaching unit or learning phase (Arras/Kecker 2016: 393f.).

Although both forms can be carried out using questionnaires or quantitative methods of data collection (i.e. by measuring results or attitudes in numbers), qualitative methods are more frequently used for formative evaluations in order to record the attitudes, opinions, self-assessments etc. of those involved.

Even though it often seems easier to implement and interpret quantitative methods and to record learning progress in evaluations, this does not always make sense. After all, teaching and learning are processes that are shaped by the individual actions of teachers and students (Arnold et al. 2018: 399). As a result, the quality or suitability of educational programmes such as VE projects can change through the individual actions and learning process of students or study groups and depends on personal and individual requirements as well as various contextual circumstances (ibid.). Consequently, there is no real cause-and-effect relationship between objective criteria and subjective learning outcomes. Evaluations should therefore revolve around individual students rather than technology and outcomes and should be based on the action research model.

A further distinction can be made between internal (self-evaluation) and external evaluation (third-party or peer evaluation) (cf. Arnold et al. 2018: 404). These forms have different advantages and disadvantages (e.g. in terms of proximity to actual teaching practice). For example, those conducting a self-evaluation are unable to distance themselves from the object of evaluation in a truly objective manner, which makes a distanced, critical and reflective view all the more necessary (see “Introduction”).

You should therefore clear up the following requirements and framework conditions before starting your (self-)evaluation (adapted from DeGEval 2004: 7f.):

- Do you have no preconceived ideas regarding the evaluation results or do you already have certain expectations?

- Can changes be made during the VE project (in terms of the aspects to be evaluated) and is everyone involved in the process willing and able to implement changes?

- Can decisions be made by the evaluators themselves (based on the evaluation results)?

- Who will be responsible for each task involved in the evaluation? Are there any external parties (e.g. colleagues) who will be able to take on certain tasks (e.g. analysis/interpretation)?

- Is there a basic level of transparency and trust between those involved in the evaluation? (For example, trust between teachers and students, between teachers themselves and towards any external parties involved is necessary to ensure honest responses.)

- What resources (technical, human, time and, if necessary, financial) are available for the evaluation?

- What conclusions and recommendations are you hoping to draw from the evaluation and who will implement them?

If you want to further process or disseminate the evaluation results for research or other purposes, you should also clarify the following points:

- What data are you allowed to collect? (Approvals may be required, e.g. from an ethics committee.)

- Who will be allowed to access and use the data that is collected? (You should clarify and agree who is allowed to view and, if necessary, publish each piece of data. For this purpose, consent must also be obtained from the students and teachers.)

- Will you be able to ensure data protection and anonymisation? (It must not be possible to trace back personal data to individual students, and data must be stored anonymously in a secure location, etc.)

2.3 Evaluation focal points and dimensions

Even though evaluations often aim to obtain an overall impression of the success of a VE project, they can only ever focus on excerpts or specific aspects. It is therefore important to identify the specific objectives of your evaluation and its main focal points or dimensions.

5. Activity:

Below you will find a list of evaluation dimensions (expanded based on Arnold et al. 2018: 398).

In principle, you can look at a VE project in terms of its concept/design (tasks, materials, etc.), results (outcomes or outputs) or processes (learning processes, approaches, use of materials, etc.).

Think about which of these dimensions/focal points are particularly important to you when evaluating your VE project. Which of them have you not considered yet?

Concept / Design

- Learning content (meets professional requirements and reflects students’ prior knowledge)

- Usability (ease of use and user-friendliness of tools)

- Acceptance and satisfaction (with regard to materials, tools, collaboration, etc.)

- Opportunities for participation (active involvement and inclusion of all students)

- Cost-benefit ratio (e.g. compared to other methods/projects)

- Media didactics (media/materials designed and used in a manner that promotes learning)

Results/learning and teaching objectives

- Achievement of learning/teaching objectives

- Critical discourse literacy (is promoted)

- Intercultural skills (are fostered)

- Learning skills (are developed)

- Learning performance (progress is made/knowledge is acquired)

- Learning effectiveness (skills acquired can be transferred and applied to other contexts)

- Group differences (differences between subgroups in terms of learning processes, communication, cooperation, participation, etc.)

Process

- Commenting on learning outcomes (students and/or teachers can and do comment on learning outcomes)

- Learning time (the time required is appropriate for the learning performance/learning objective)

- Learning actions (students act in a manner that helps to meet the learning objectives and drive the learning process)

- Support (students receive appropriate support during the learning process)

- Communication (appropriate exchange of information between students themselves and between students and teachers)

- Cooperation (students work successfully together and collaborate on tasks and/or project outcomes)

When planning your evaluation, select individual dimensions and then flesh them out by formulating central questions and any hypotheses you may have. There should be theoretical and practical reasons behind your selection. For example, if you want to look at the results of your VE project, you should first think about the following: What could the results of the VE project be? What do you want to measure or find out? You should focus on short-term or medium-term results and be specific. This will ensure that your question can actually be answered. For example, you could consider which specific aspect of critical discourse literacy is to be developed (e.g. critical examination of Internet sources) and exactly how this could be demonstrated in the context of the VE project tasks (e.g. by addressing the reliability of a source in group discussions).

6. Activity:

Write down three dimensions that are particularly important to you in your VE project and briefly explain your selection.

How to write questions

Questions are important to ensure that evaluations can be conducted and developed in a targeted manner. Good questions focus on specific topics and are phrased in an understandable and answerable manner. A good question will also help you set boundaries: What should not/cannot be examined in the evaluation? (cf. QS 29: 25).

2.4 Example: evaluation of learning/teaching objectives

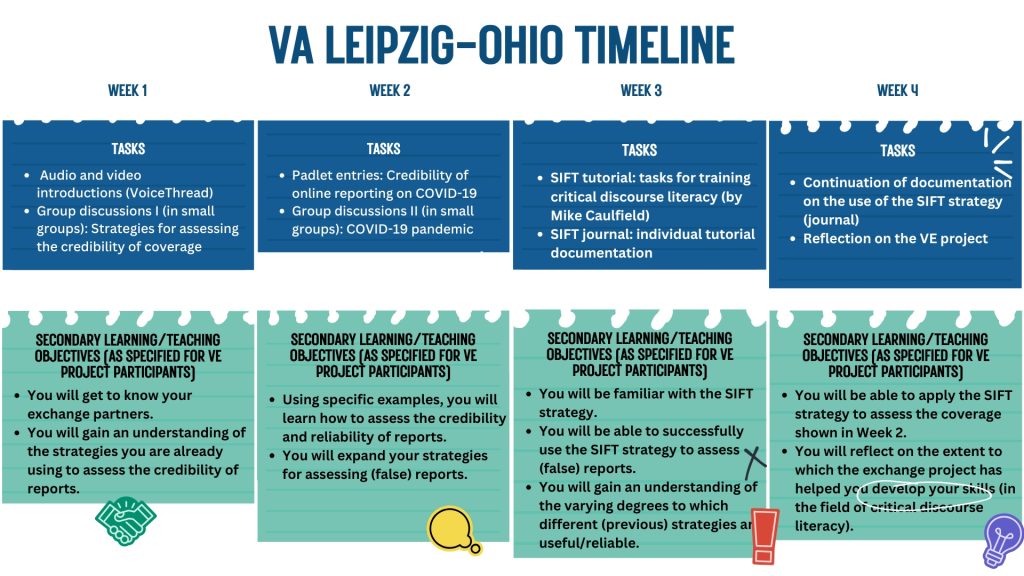

In the summer semester of 2020, a virtual exchange project was held between students enrolled in two different bachelor’s seminars at Leipzig University (Germany) and Ohio University (USA) (see good practice example „COIL zu Critical Media Literacy: Leipzig – Athens“). The overarching goal of the VE project was to promote critical discourse literacy (CDL) among participating students from both universities: “The goal of the exchange was to jointly develop students’ CDL via several asynchronous online tasks including discussions, tutorials, and reflections” (Ketzer-Nöltge/Markovic 2022: 126). Critical discourse literacy is a subdomain of general media literacy. In this example, the term refers primarily to the ability to distinguish fact-based reporting from fake news and to discuss and reflect critically on the topic. The students were given a specific, primary learning/teaching objective: “You will be familiar with and able to apply strategies to assess the credibility of media reports”

To achieve this overarching goal, various tasks were developed and materials made available for the duration of the project, which lasted four weeks, as presented in the following table (cf. Ketzer-Nöltge/Markovic 2022: 130). The secondary learning/teaching objectives can also be found in the bottom row of the table.

Link to SIFT-Tutorial (Mike Caulfield): https://www.notion.so/Check-Please-Starter-Course-ae34d043575e42828dc2964437ea4eed

If a VE project has been planned in such a way that secondary learning/teaching objectives – which may even build on one another – are to be achieved in different phases of the project, you should ensure that each of them is actually achieved. If they are not achieved, you need to find out which changes in project implementation are necessary and useful. In addition, at the end of a VE project implementation cycle, lecturers usually want to know whether the primary learning/teaching objectives have been achieved, how the students view the project as a whole, and whether any changes or improvements are necessary for the next cycle.

7. Activity:

You should think about what specific questions you could ask to evaluate the project in question. What questions could you ask in a formative evaluation and what questions could you ask in a summative evaluation?

Depending on the project and learning/teaching objectives, hypotheses can be formulated for each question, e.g. “Integrating communicative reflection tasks (e.g. answering a reflection question and enabling student interaction in an Internet forum) results in better learning outcomes when it comes to promoting critical discourse literacy”.

All illustrations on this page by @storyset (https://www.freepik.com/author/stories)

translated by: KERN AG, Sprachendienste Leipzig

This work © 2024 by Prof Dr Almut Ketzer-Nöltge is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0