3. (De-)Constructing Stereotypes

Stereotypes are a natural way for humans to make sense of the world, both in their construction of identities (i.e., understanding yourself to be a member of a group) and when interacting with people that appear to be different. However, as they are inherently simplified notions of complex realities, they may lead to biased attitudes and discriminatory behavior.

A common learning goal of VE projects is to foster cultural competences by (de-)constructing stereotypes. First, by raising awareness for generalized concepts that VE participants already have of a specific (cultural/national/religious/…) group. Next, these notions are challenged, for example by contrasting these ideas through interaction with actual individuals from such groups.

3.1 Digging Deeper into the Danger of a Single Story

The following activity takes a closer look at a video frequently used to initiate (de-)constructions of stereotypes in VE projects. Instead of only engaging with the main message of the video – the possible negative impacts of oversimplified characterizations – the activity engages with a specific passage in greater detail. This passage uses specific examples to illustrate the relationship between stereotypes and power.

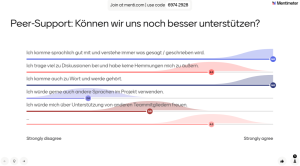

4. Reflection Activity: What makes a good kick-off to a VE project?

Take notes on the expectations you have for the initial phase of a VE project in your field. What matters to you as an educator? What should your learners experience?

A common approach to VE projects is the progressive model (O’Dowd/Ware 2009) consisting of three distinct phases. The first phase, information exchange, broadly serves the purpose of breaking the ice between participants to facilitate the collaborative processes throughout the project duration. Research, including our own data and experiences (Öztürk 2022, Ekin 2023), suggests that this structure should not be misunderstood as a linear progression from superficial small talk to profound exploration. In fact, sometimes the opposite can be the case: the open nature of icebreaker activities can create relatively free discussion spaces with unexpected results. At any rate, this preparatory phase is generally considered as conducive to rapport building (Müller-Hartmann 1999: 178).

A highly popular learning material in the context of both icebreakers in VE projects as well as cultural learning initiatives in general is the 2009 TED Talk “The Danger of a Single Story” by Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Commonly, the 19-minute video – which contains anecdotes on people living in places including Nigeria, the United States, Mexico, India, Namibia, and Israel/Palestine – is used to spark thought processes and discussions about stereotypes that participants (may) have in relation to their exchange partners (i.e. hetero stereotypes). In addition, participants may be asked to anticipate the stereotypes their partners may subscribe to. This can lead learners to examine how the cultural groups they belong to may be represented, for example in the media, or to critically examine how they see themselves (i.e. auto stereotypes).

While these approaches largely focus on the top-down knowledge the participants have of the world and its inhabitants, engaging with the content and substance of the video in a more targeted bottom-up manner can offer a starting point into critical engagement with power structures.

For example, the section from 9:25 to 10:50:

[…] So that is how to create a single story, show a people as one thing, as only one thing, over and over again, and that is what they become.

It is impossible to talk about the single story without talking about power. There is a word, an Igbo word, that I think about whenever I think about the power structures of the world, and it is “nkali.” It’s a noun that loosely translates to “to be greater than another.” Like our economic and political worlds, stories too are defined by the principle of nkali. How they are told, who tells them, when they’re told, how many stories are told, are really dependent on power.

Power is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of that person. The Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti writes that if you want to dispossess a people, the simplest way to do it is to tell their story, and to start with, “secondly.” Start the story with the arrows of the Native Americans, and not with the arrival of the British, and you have an entirely different story. Start the story with the failure of the African state, and not with the colonial creation of the African state, and you have an entirely different story.

5. Reflection Activity: Mentoring a controversial dispute

Have a look at the following short excerpt from a much longer, more complex interaction between VE students located in Israel (blue) and Germany (orange) that occurred in the summer of 2024. It was the result of an icebreaker activity based on the ‘Danger of a Single Story’ TED Talk, as described above. One of the students reached out to the teachers, asking for guidance.

Source: own figure based on an actual student exchange in 2024

Comment on the exchange with the help of some of these guiding questions:

- How could you support the students?

- Which knowledge of German/Israeli/Palestinian history may help you – or may be required – to engage productively and respectfully?

- What would you like to know about the individuals and their identities in this exchange to better help them specifically?

- How may the excerpt from the TED Talk support you?

Both students likely need to learn more about each other’s individual perspectives, backgrounds, and (cultural) histories. The student located in Israel may not be (fully) aware of the concept of German Erinnerungskultur (memory culture), particularly in terms of its strong connection to the atrocities committed in Nazi Germany during the Holocaust: Connected with the notion of Staatsräson (reason of state), people in Germany may have a particularly strong sense of guilt and/or responsibility when discussing matters related to the state of Israel. Criticism of Israel, in particular, may be a highly sensitive and uncomfortable topic, with divergent sets of knowledge available to different speakers based on their education.

The student located in Germany, on the other hand, may not be sufficiently familiar with the complex histories and realities of the geographic region between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, i.e. today’s state of Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories. For example, if the exchange student located in Israel identifies as an Arab Israeli and/or Palestinian, it is likely that their cultural identity is in part informed by the Nakba, that is the violent displacement and dispossession of Palestinians and their properties since the establishment of Israel. Further, they may have friends or relatives living in the occupied territories who are subjected to various control measures including checkpoints and surveillance systems enforced based on color-coded ID cards.

Either way, the students should be encouraged to acquire background knowledge for more informed opinions, both through individual research and with the help of materials curated by the teachers. Further, it makes sense to encourage them to acknowledge how the conversation topic may be highly emotionally charged. This can impede engaging with the topic in a critical, constructive, and curious manner. As section 5 of this module will show, agreeing on specific codes of conduct may be advisable.

3.2 Understanding Unintended Consequences

While a deep dive into the cultural histories of your exchange partners (and yourself!) may not be your primary interest in VE, cultural differences and similarities are likely to impact the ways in which students and teachers interact. In some cases – for example during an exchange between participants located in Israel/Palestine and Germany – historical entanglements and unforeseen events may make it necessary.

Research conducted at Beit Berl College, Israel, during the COVID-19 pandemic has further found that an increased focus on nurturing the social-emotional competences of students is needed to better prepare them for disruptive events. Raising awareness for the causes and consequences of disruptions may help nurture resilience (Hadar et al. 2020).

Several concepts have been created to better grasp the world humans inhabit in the 21st century. VUCA is one such attempt, combining four circumstances considered highly influential on people’s lived experience (Hadar et al. 2020: 573):

For educators seeking to prepare learners to face these realities – be it in their future careers, personal lives, or within wider social and democratic processes – becoming aware of such concepts can be a meaningful first step towards selecting adequate teaching materials and designing educational interventions, including VE projects. In the case of the VE project mentioned in the introduction, we could not predict that a crisis like the Sheikh Jarrah controversy and resultant violence would loom over our project. At the same time, having the project be based on direct engagement with ‘global issues’ within the framework of the UN SDGs also meant that we could not turn a blind eye to it.

3.3 The Beutelsbach Consensus

When faced with controversial matters, educators may struggle to identify the best way forward. The Beutelsbach Consensus from 1979 is one attempt at providing guidance for teachers. It is a minimal consensus agreed upon at a conference on the role and responsibility of civic education in Germany. A central point of contention was whether civic education should stabilize a given political system or enable changing it. The consensus consists of three principles (bpb 2012):

The next chapter will explore ways in which the second principle, in particular, can be accounted for.

All illustrations on this page by @storyset (https://www.freepik.com/author/stories)

This work © 2025 by Fabian Krengel is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0